Who is ‘Ain al-Hilweh? I ask not because I am interested in the answer, if we were to believe it exists, but for the reason that demanding one is enough to set a process of research in action. The title is a play on words highlighting the uneasiness that accompanies attempts at defining what places are. It combines the question of “what is ‘Ain al-Hilweh?” as a material, administrative, and social entity with “who produces ‘Ain al-Hilweh?” as a social space.

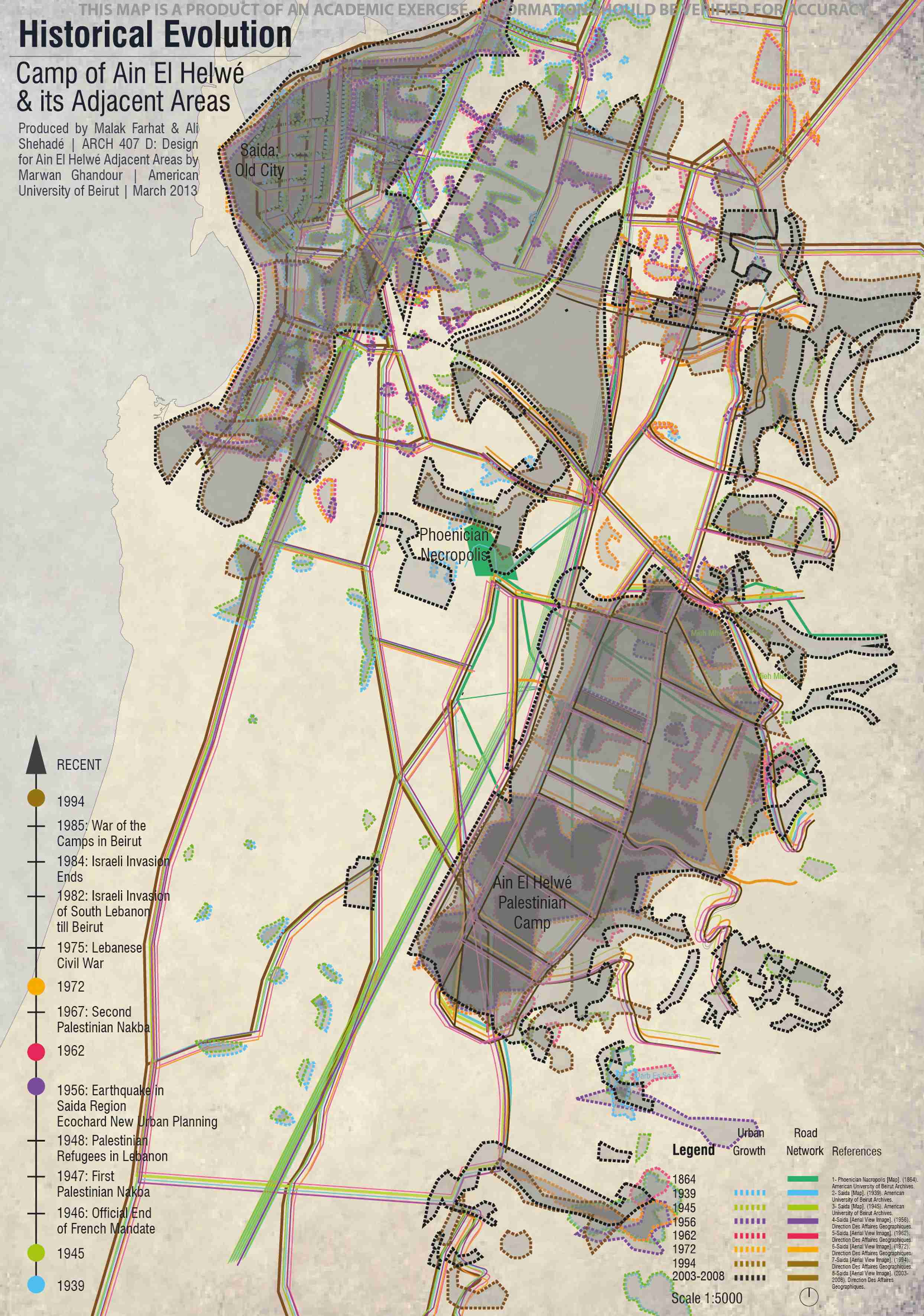

Geographically, ‘Ain al-Hilweh is the area southeast of the port city of Saida, which historically was the site of a Phoenician necropolis in ancient times and a French Military camp during the French mandate of Lebanon. In 1963, a governmental publication referred to ‘Ain al-Hilweh as Saida al-Jadida (New Saida), considered as contemporary extension of the old city.[1] In popular discourse, however, ‘Ain al-Hilweh is a reference for the Palestinian camp that it contains. With an estimated population of more than sixty-six thousand, the ‘Ain al-Hilweh camp is the largest camp in Lebanon. The camp was originally settled by refugees displaced from northern Palestine in 1948, officially established in 1949, and managed since 1950 by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). As a mostly informal settlement, the camp and its adjacent neighborhoods accommodated over the years other refugees and a mix of individuals of different backgrounds and nationalities that sought a reasonable alternative to living in the city proper.

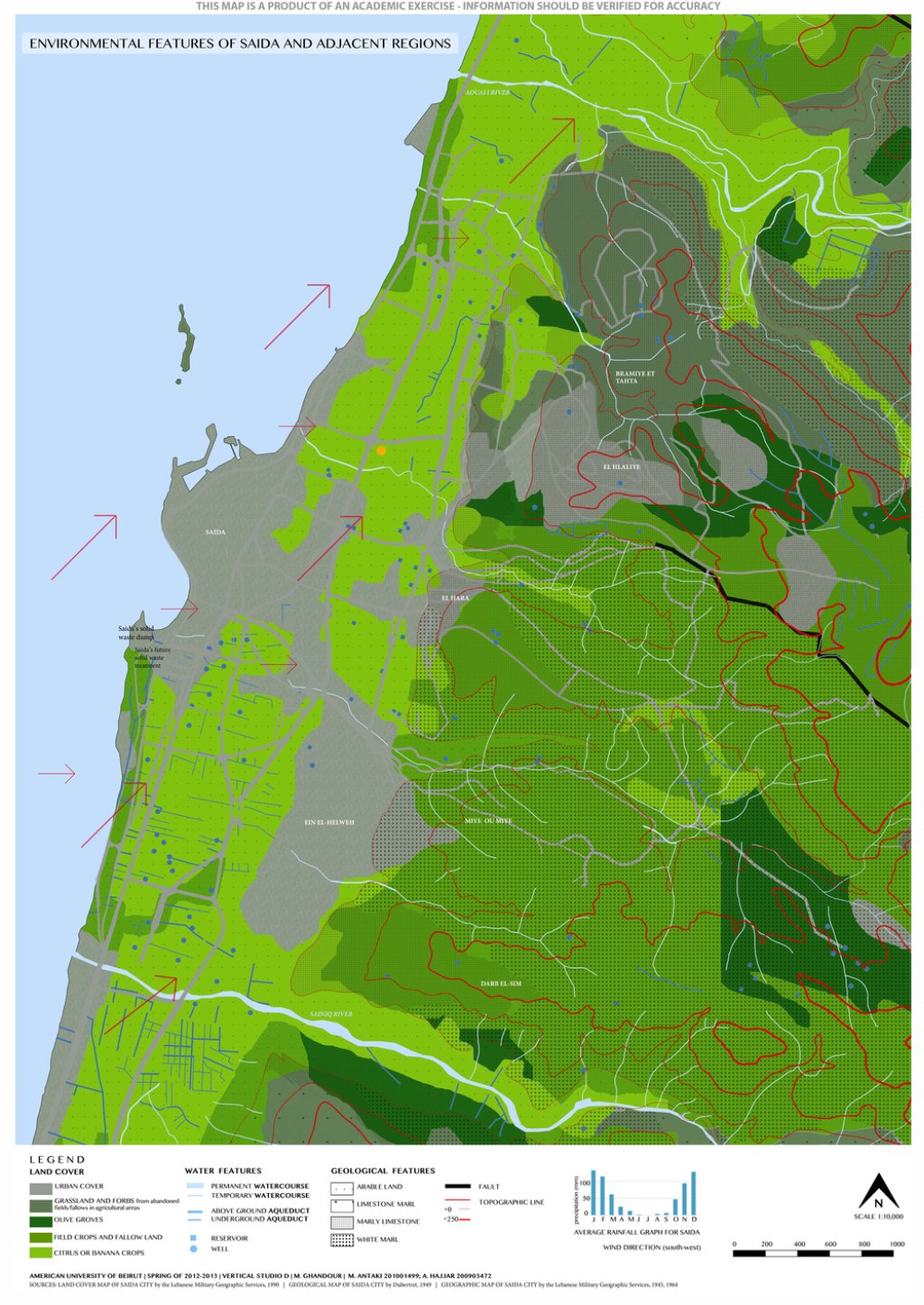

‘Ain al-Hilweh is part of a larger agglomeration of neighborhoods that constitute the metropolitan city of Saida. Neighborhoods belong to different municipalities, which constitute a microcosm of the Lebanese world of sectarian diversity. Within the six kilometers that separate the Awwali river to the north and Sanniq stream to the south, Saida`s population is distributed over the municipalities of Saida, Darb al-Seem, Miyeh wa Miyeh, Haret Saida, Hlaliyeh, Bramiyeh, ‘Abra, and Majdilyon to name most. Within this administrative complexity, Palestinians of ‘Ain al-Hilweh camp have coexisted among Lebanese Sunni, Shiite, Catholic, Maronites and Jews. ‘Ain al-Hilweh is divided between the municipalities of Saida to the west and Darb al-Seem and Miyeh wa Miyeh to the east. Hence, service provision for these neighborhoods require coordination with UNRWA and the three municipalities, each of which carries its own funding sources as well as social and political priorities.

[Figure 1: Environmental Features of Saida and Adjacent Regions by MaryLynn Antaki and Azza Hajjar.

“Building Informal” design studio at AUB, Spring 2013. Click on image to view larger map.]

In the spring of 2013, I worked with fourteen architecture students from the American University of Beirut (AUB) on mapping ‘Ain al-Hilweh and proposing architectural and urban interventions in the area.[2] In addition to the nine visuals that are included, I attempt to answer the title question three times in the text, each time by engaging a view of ‘Ain al-Hilweh from a different location. The first location is Paris, where a master plan for the area was developed in 1956 by the office of Michel Ecochard. The second is Ta‘meer, a predominantly Lebanese public housing neighborhood built in ‘Ain al-Hilweh in the early 1960s. Finally, the third location is within the security zone that engulfs ‘Ain al-Hilweh Palestinian refugee camp and ten adjacent neighborhoods. These narratives are informed by the work of the students, on-site conversations and documents collected from multiple individuals. These resources are not by any means comprehensive or exhaustive, but rather the text is a subjective account of my relatively brief encounter with the place. As in any urban environment, ‘Ain al-Hilweh continues to be created and continues to have hidden identities and narratives, yet to be uncovered, that claim their position in its overall identity.

The View from Paris

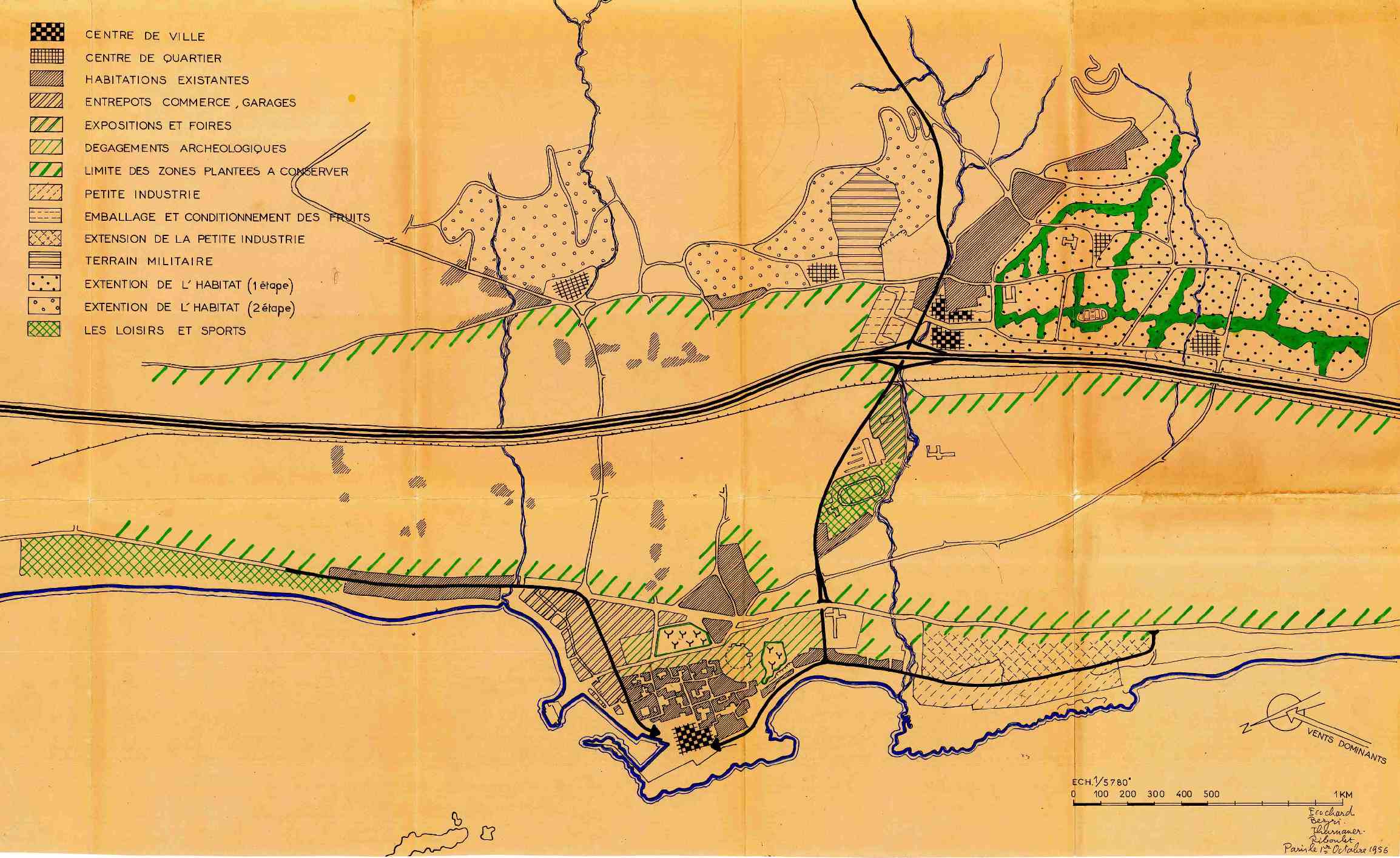

Michel Ecochard, the French architect who had fabricated the earliest master plan for Beirut and Damascus, and his team saw ‘Ain al-Hilweh as the future extension of Saida. Their project for Saida`s master plan was developed during the aftermath of the 1956 earthquake that had left areas in the old city of Saida partially or fully destroyed. The project would preserve the historical orchards that separate the coast from the foothills to create a north-south open green corridor, with old Saida neighborhoods and fishing port to its west and new, modern developments merging with the small towns on the foothills to the east. On the map, the green corridor is punctured only once with the projected sports and entertainment facilities that link ‘Ain al-Hilweh with old Saida. A proposed north-south highway parallel to the existing railway serves the area using the main interchange station at the northwest edge of ‘Ain al-Hilweh.

[Figure 2: Masterplan of Saida by Michel Ecochard and his team. Map is hand colored blueprint with the following hand-written list of names in the lower right corner: [Michel] Ecochard, [Amin] Bezri, [Gerard] Thurnauer and [Pierre]Riboulet, and dated “Paris, le 1er Octobre, 1956.” Amin al-Bizri Archives, courtesy of Fadi Kotob. Click on image to view larger map.]

At the time, ‘Ain al-Hilweh must have seemed a convenient future neighborhood of modern living, resting at the foothills, overlooking the orchards and sea coast beyond, connected with multiple modes of transportation with sports and entertainment facilities in the vicinity, in addition to an existing (French and later governmental) hospital and a school (later to be known as Za‘tari public school). The Ecochard team anticipated the ‘Ain al-Hilweh neighborhood as the first of two phases of urban growth in Saida. The second phase was to expand two main areas north of ‘Ain al-Hilweh, the village of Haret Saida and the villages of Qiya‘, Hlaliyeh and Bramieh. As shown in the project documents, the areas of the neighborhoods in phase one were to be seventy-seven hectares in ‘Ain al-Hilweh with twenty-two and twenty-one hectares in phase two, respectively.[3] Compared to the areas of phase two, the urbanization of ‘Ain al-Hilweh had a more urgent status primarily from the earthquake disaster relief effort, as well as for a de-densification project of the old city, where certain neighborhoods were deemed overcrowded and unhealthy.[4] Accordingly, ‘Ain al-Hilweh area was targeting lower income groups of Saida as reflected in the proposed density of one hundred-fifty persons per hectare. The phase two neighborhoods were set at one hundred persons per hectare.

The 1956 map produced in Paris does not include the then eight-year-old Palestinian refugee camp spread on close to fifty percent of the area of phase one (thirty-seven hectares). Also absent from the map is the “Nawar” encampment that used to materialize on a seasonal basis in makeshift houses next to the railroad (also known as Sekkeh). While the absence of both camps might have been a result of considering that camps are by nature transient, it also indicates the shortcomings of modern urbanism in addressing complex social and spatial environments. Indeed, the ‘Ain al- Hilweh Palestinian refugee camp played a major role in the future urbanization of Saida, where currently a set of residential neighborhoods, numerous educational and public institutions connect the historical city of Saida to ‘Ain al-Hilweh. Moreover, the Nawar houses are still constructed in a similar manner sixty years later, albeit with recycled tin sheets and car tires, while having a more permanent presence.

[Figure 3: Historical Evolution. Map by Malak Farhat and Ali Shehadé. The map was created by overlaying urban areas traced from multiple historical aerial views, and maps of Saida and its region. “Building Informal” design studio at AUB, Spring 2013.

Click on image to view larger map.]

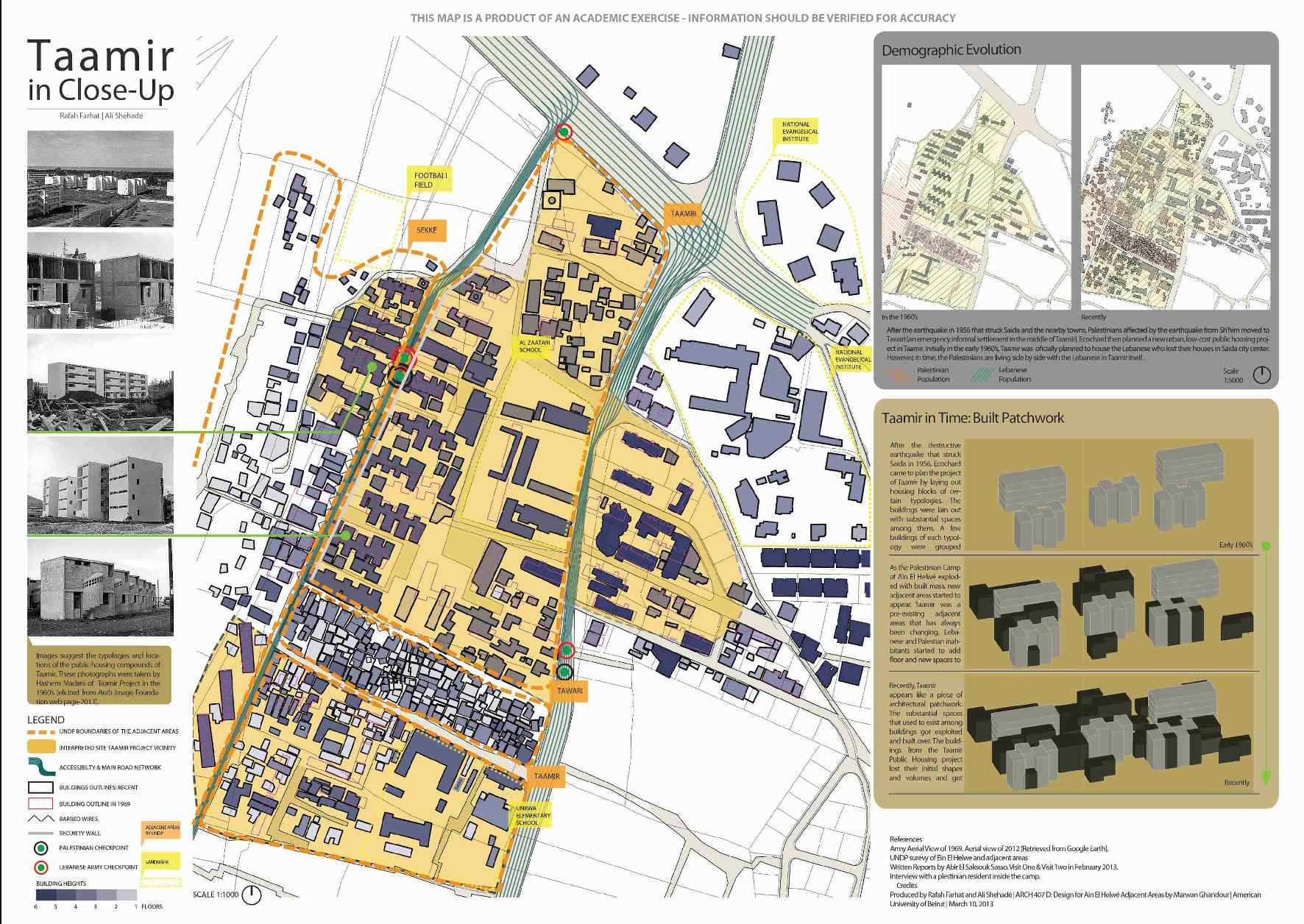

It is still unclear to me what was executed from the Ecochard team master plan. While the existing buildings seem to follow the Ecochard architectural drawings, the current overall urban layout does not fully match Ecochard’s master plan. However, Ecochard`s study resulted in, arguably, the construction of the largest public housing project in Lebanon, which would include middle to low income Lebanese families housed in proximity to the largest concentration of the Palestinian population in Lebanon. This Lebanese neighborhood by the camp, mostly completed in the early 1960s, would be called Ta‘meer (re/construction in Arabic) in reference to the board, Idarat al-Ta’meer, which was created to manage the project.

The View from Ta‘meer

‘Ain al-Hilweh nowadays has a concentration of more than seven hundred and fifty persons per hectare, more than five fold what Ecochard projected in 1956. This was a result of the existing population growth and the thick influx of other refugees and low-income residents into the camp within ‘Ain al-Hilweh, a phenomenon common to other Palestinian camps in Lebanon. Given that camps have fixed boundaries designated by the UNRWA`s lease of private and public properties, the increase in population has been densifying the urban environment of the camp with new multi-story buildings within these boundaries. Similar building activity occurred in the unbuilt areas outside the camp boundaries generating new adjacent neighborhoods with a majority of Palestinian residents. The densification of ‘Ain al-Hilweh is also a result of the rapidly growing population rate of the Ta‘meer neighborhood where residents have been making additions to mid-century building blocks. Similar to other modern public housing of the era, these blocks were designed to have minimal footprint with efficient circulation and spatial configuration. The majority of the Ta‘meer blocks are four floor walkups with four to eight apartments per floor. There are also smaller two floor houses, but these are less common. Unlike the four by four meters room size that is commonly known in vernacular residential units, the apartments designed by the Ecochard team were based on room dimensions of 2.44 to 3.05 meters wide intended for multiple family members. Since the 1970s, residents of the blocks have been expanding (mainly) horizontally, adding rooms and balconies to an otherwise very tight apartment. By the 1980s, this practice became more common in the absence of oversight or policing during the 1975-1990 Lebanese civil war. The expansions accommodated family growth and created more spacious apartments with large balconies used for social gatherings. Since the residential blocks were spaced apart, the additions intruded onto common garden spaces without impacting the views or ventilation of the neighboring blocks.

[Figure 4: Ta‘mir in Close-Up, by Rafah Farhat and Ali Shehadé. “Building Informal” design studio at AUB, Spring 2013.

Click on image to view larger map.]

The Ta‘meer neighborhood still attests to the current strong presence of working class families that are historically affiliated with the Saida Nasserist political leader, the late Maarouf Saad. There are more posters of the Saad family in Ta‘meer than one sees in the rest of Saida. In his time, Saad attempted to unify the working class by politically and financially supporting civil institutions and associations, and by lobbying officials to provide affordable housing and services. Saad was assassinated in 1975 during a fishermen`s demonstration in Saida. The western-most four residential blocks of Ta‘meer are called "Bahriyeh" (fishermen in Arabic), because Saida’s fishermen families, a group of people that were closely connected to Saad, inhabited them. People still regularly talk about the way he encouraged families to invade and settle in the building blocks prior to their completion because the government was not responding to their requests, even though the apartments were built for these families to be owned with a low mortgage rate.

As it happened, Mr B, who is in his eighties and owns one of the larger apartments in Ta‘meer, told me that it took him twelve years to be able to move into an apartment. Mr B was displaced from Rjail al-Arb‘een neighborhood in old Saida because his house was destroyed in the 1956 earthquake. He was given temporary accommodation in emergency barracks (which people later referred to as “Baraksat”) constructed by the government in the vicinity of the nearby French Hospital. He was given a five by five meters room with no services. Like the rest of the residents in the barracks, he had to build a kitchen and bathroom next to the room. For more than twelve years, he lived in the barracks. Mr B and his wife moved in with one child and moved out with seven, five boys and two girls. It was not until 1972 that Mr B secured ownership, with mortgage, of a Ta‘meer apartment. In the process, Mr B talks about stories of corruption and nepotism that included a variety of political figures of Saida, Beirut and the South, including Maarouf Saad and his followers. In 1982, Mr B made an addition to the apartment. Residing on the third floor, the families in the lower two floors agreed to the project and eventually the owner of the fourth floor asked to join in, realizing they can benefit from these surface areas too. The addition doubled the apartment area and provided a spacious kitchen, living room and balcony. Mr B claims that he informed an official in the Serail of Saida (the administrative institution in charge of South Lebanon governorate) about the addition, whose only condition was not to intrude onto the sidewalk.

[Figure 5: Mr B apartment as seen from the Za‘tari school building. Photograph by Akram Zaatari, 2013.]

A Palestinian builder who Mr B fervently testifies to his building prowess constructed the addition. Mr B claims that the builder constructed a massive 1.2 meters reinforced concrete cube for the foundations of the building addition columns. Palestinians in ‘Ain al-Hilweh have a strong reputation of providing skilled labor to the region in agriculture and construction, mostly the latter in recent decades. Their relationship to the Lebanese community residing in Ta‘meer is much more intimate than to the rest of Saida residents. But, the Ta‘meer residents feel that they are more abandoned and marginalized than the residents of the camp itself, as humanitarian funding and international efforts, when they happen, are usually directed to alleviate the living conditions of the Palestinian refugees. Throughout the decades, Ta‘meer`s residents were able to experience the history of their Palestinian neighbors because of their close proximity to them. The camp, and Ta‘meer by extension, went from being a center of power in the seventies, when the camps were the center of Palestinian struggle managed by the well-funded Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) led by Yasser Arafat, to being a target for destruction in the 1980s, with the Israeli invasion of 1982 and the war of the camps of 1985, led by the Syrian-backed Amal movement. Finally, like the camp since the mid 1990s, Ta‘meer became a marginalized and enclosed neighborhood adept to harboring extremist movements.

The View from Within the Security Zone

Fadel Shaker, the notorious Lebanese pop singer represents this close relationship between the two communities. Shaker was raised in Ta‘meer to a Palestinian mother and a Lebanese father, and later married a Palestinian woman. Shaker went from singing in Ta‘meer and in the camp, to Arab stardom during the nineties, only to recently return to Ta‘meer as a wanted militant by the state. Shaker had renounced his pop career to join the extremist Salafi movement, impregnated with sectarian hostility.

Ta‘meer and the camp play complementary roles in the lives of the ‘Ain al-Hilweh residents. On one level, the camp includes busy markets for affordable foods and goods serving the area, which created an organic continuity with its surroundings. On another level, the camp and most of the adjacent neighborhoods are enclosed within a security zone, successively guarded by the Lebanese army and the Palestinian Security Committee, which separates it from the Ta‘meer neighborhood. Indeed, ever since the Cairo Agreement of 1969, Palestinians have the right to carry arms on camp’s grounds, which allowed fugitives like Shaker to have relative protection from state authorities. During the aftermath of the conflicts in Ta‘meer in 2006 and 2007, the Lebanese army raided the neighborhood looking for Islamic militants, and intensified the security of all the gates to the camp. As a result, the presence of Islamic militants became concentrated within the camp in proximity of Ta‘meer, mainly in the Taware‘ neighborhood where Shaker is suspected to be hiding. The hunt for these fugitives usually requires coordination between the Lebanese army and the Palestinian Security Committee, which includes representatives from camp militias. The camp may act as a safe haven for people wanted by the army, but for some of its Palestinian residents, it is the area outside the camp that represents a possible escape from the vicious cycle they are living in.

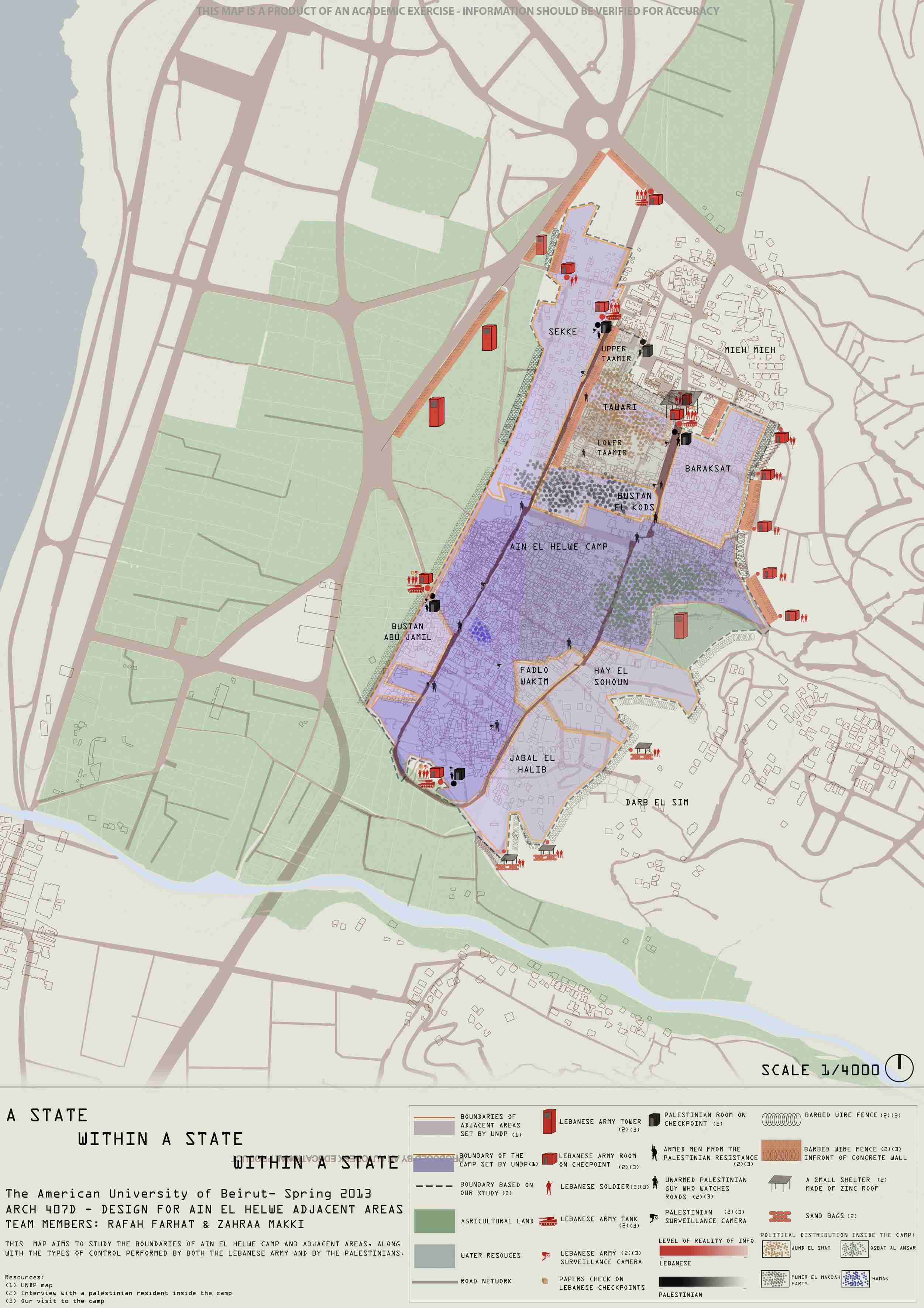

[Figure 6: A State Within a State Within a State, by Rafah Farhat and Zahraa Makki.

“Building Informal” design studio at AUB, Spring 2013. Click on image to view larger map.]

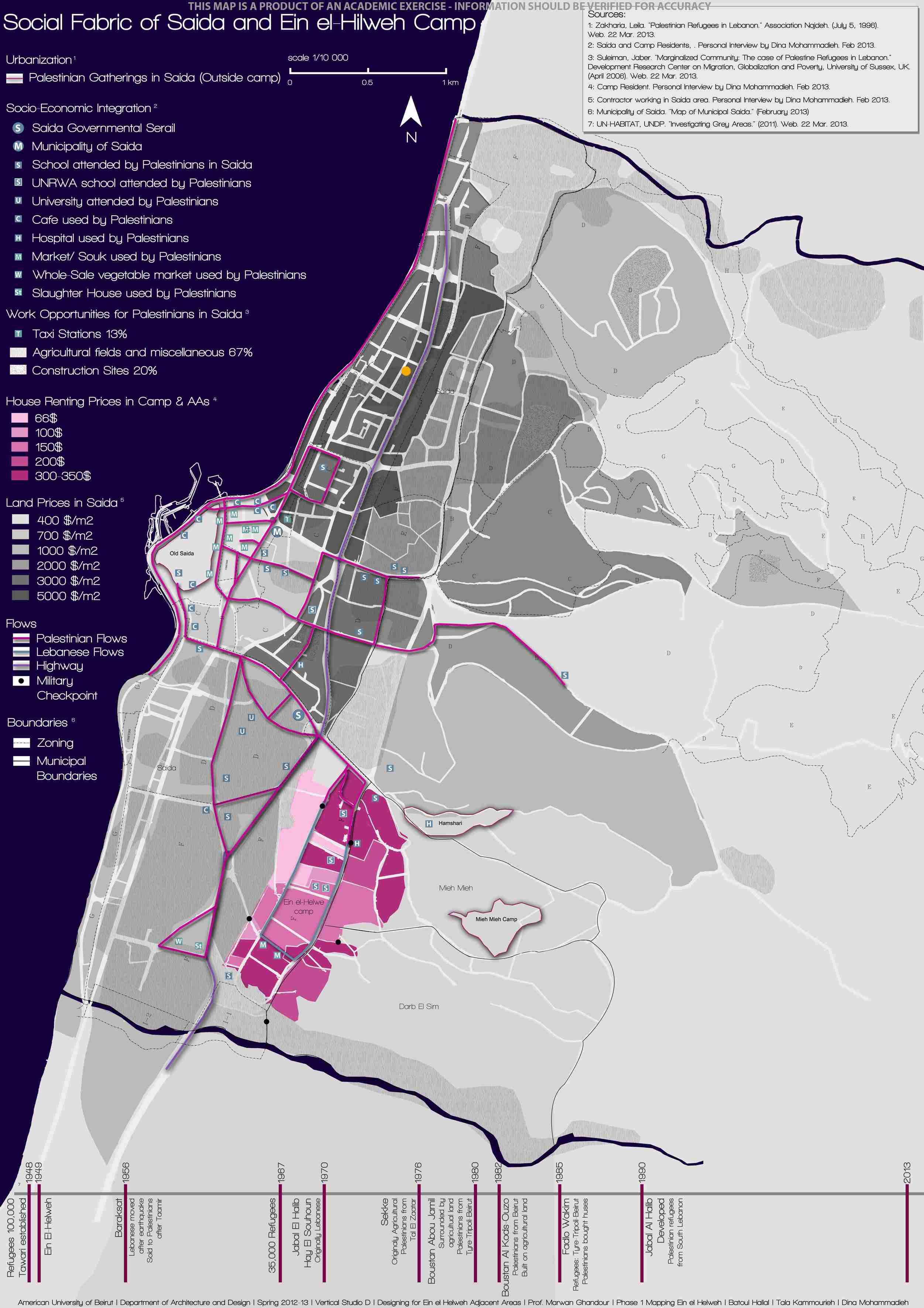

L is a fifteen-year-old camp resident who attends Za‘tari public school located a few meters outside the northern checkpoint to the camp. Throughout his early life, his parents made sure that he would not attend an UNRWA school within ‘Ain al-Hilweh camp to “protect” him from the “ultimate predictable fate” of his peers. L talks about the abundance of arms in the hands of his friends supplied by the militia, or sometimes by their parents for extra protection. They envy him, he says, for attending Za‘tari school. They hardly ever attend their UNRWA school. He says that most pretend they are going to school in the morning, only to spend the day roaming around the camp. A good number of school kids end up enlisting in one of the militias, he adds, where they attend meetings at the party headquarters, and practice using and “cleaning” machine arms.[5] After school, L spends his time with his friends playing football in Mal‘ab al-Ahmar (the red football field), to the west of the camp, smoking and pursuing girls. But L insists that he only pursues girls outside the camp, mainly at the seaside corniche of Saida, because if he was to do so inside the camp, the girls’ parents could cause him a lot of trouble.

[Figure 7: Social Fabric of Saida and ‘Ain al-Hilweh Camp. Map by Batoul Hallal, Tala Kamourieh and Dina Mohammadieh.

“Building Informal” design studio at AUB, Spring 2013. Click on image to view larger map.]

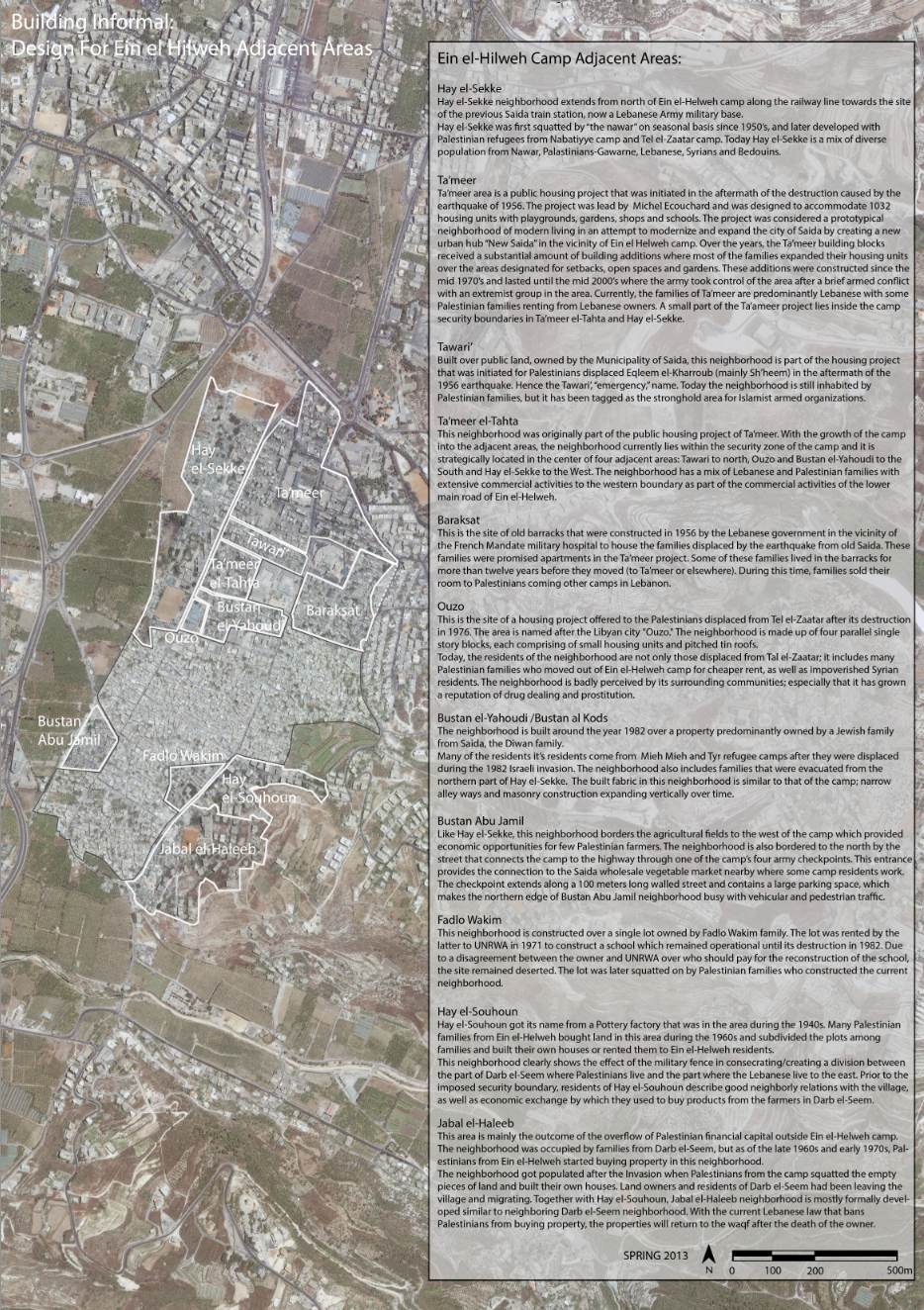

L lives in Jabal al-Haleeb, a neighborhood southeast of the camp proper but that lies within the security zone established by the Lebanese army. Indeed, ‘Ain al-Hilweh camp is surrounded by twelve neighborhoods that could be considered its extension, one of them the aforementioned Ta‘meer neighborhood. Ten of these neighborhoods are included within the security zone. It is not clear how the boundaries of the security zone were established, as it happened over more than two decades ago where, progressively, checkpoints were stationed, barbed wire fences were established, walls were constructed and watchtowers were put up. The Ta‘meer neighborhood and the Villât neighborhood nearby (from the Arabic plural of “Villa”), which are to the north and northeast, were kept out of the security zone. The population of the ten neighborhoods, included within the security zone, is predominantly Palestinian with few other nationalities included. Each of the adjacent neighborhoods has a different story of spatial production (as we saw in Ta‘meer) that affects its current condition and the population that inhabits it. Similar to the camp, most of the neighborhoods were urbanized informally with similar spatial configurations.

[Figure 8: ‘Ain al-Hilweh Palestinian Camp and its Adjacent Areas, produced and edited by Salwa Sabbagh.

“Building Informal” design studio at AUB, Spring 2013. Click on image to view larger map.]

Jabal al-Haleeb and Hay al-Suhûn to the southeast, however, include multi-story apartment buildings, some of which are owned by Palestinians with official building permits. These two neighborhoods materialize the growth of Palestinian capital in the 1970s until its decline after the 1982 expulsion of the PLO from Lebanon, the marginalization of the camps by the PLO post the Oslo agreements of 1994, and the law of 2001 where formal Palestinian investment in real estate came to a full halt. The rent cost in these neighborhoods is higher than within the official camp. Their density is lower with apartments that have distant views to the surrounding landscape. On the other hand, Hay al-Sekkeh neighborhood to the northwest has the lowest rent. Hay al-Sekkeh conserves a transient condition as a result of the makeshift houses of the Nawar as the Lebanese army ban on new permanent construction in the northern part of the neighborhood. Hay al-Sekkeh is the most diverse neighborhood in the camp including Palestinians, Nawar-Lebanese, Lebanese and Syrian inhabitants. The southern end of Sekkeh includes the red football field where L and the camp`s youth play. East of playground is the smallest neighborhood, Ouzo, that carries the social stigma of drugs and prostitution by the surrounding residents. Constructed as relief housing for Tel al-Za‘tar camp survivors in 1976, it is a neighborhood in need for desperate upgrading. To the north of Ouzo and aligned with Sekkeh is the area where political tensions periodically erupt in ‘Ain al-Hilweh, namely Bustan al-Yahudi, a.k.a. Bustan al-Qods, Ta‘meer al-Tahta and Tawari‘, where Shaker is thought to be hiding. In recent years, these neighborhoods have been witnessing recurrent, but short, armed battles mainly between the Salafist and the traditional PLO militias. Finally, east of Tawari‘ and bordering the Villât neighborhood is the Baraksat neighborhood, that originated from the emergency barracks of 1956, where Mr B lived for more than twelve years before securing an apartment in Ta‘meer.

So, I ask: Who is ‘Ain al-Hilweh? Contrary to common academic practice, I do not want to make any conclusions about this place at this stage, but present material for thinking and reflection by the reader.

[Figure 9: View from Jabal el-Haleeb towards Saida. Detail of photograph by Maylynn Pauline Antaki.]

[Acknowledgements—Many thanks to: Yumna Marwan who extensively edited an earlier draft of this text. Salwa Sabbagh for all the assistance she provided for the AUB design studio “Building informal.” Abir Saksouk-Sasso for the fieldwork she did in ‘Ain al-Hilweh camp. Ismael Sheikh Hasan for the ‘Ain al-Hilweh camp information and documents he provided me with. Nancy Hilal for all the information she provided on the Camp adjacent areas. Ahmad Gharbieh for his valuable contribution to the mapping project of the Building Informal studio. Much appreciation to Fadi Kotob for his generosity in sharing the valuable Amin al-Bizri archives. Thanks to Akram Zaatari for all his help and, as usual, inspiring engagement with the subject. My sincere and deep appreciation to Mona Fawaz for her extensive contribution to the studio discussions and her support throughout the process. Finally, my deepest appreciation to the fourteen students that took the chance to enroll in the “Building Informal” studio and brought a lot of energy, sincerity, dedication, thoughtfulness and fun to the whole academic experience. They are: Marylynn Pauline Antaki, Diana Aridi, Hikmat al-Edelbi, Laura Fallaha, Rafah Farhat, Malak Farhat, Azza Hajjar, Batoul Hallal, Ayman Jalloul, Tala Kammourieh, Zahraa Makki, Dina Mohammadieh, Ali Shehade, and Farah Zarzour.]

[1] See "مشروع إدارة التعمير في صيدا الجديدة" a booklet distributed during the inauguration of ‘Ain al-Hilweh housing project (Ta‘meer) on November 21, 1963. Amin al-Bizri archives, courtesy of Fadi Kotob.

[2] The design course is Arch 407D, Building Informal: design for ‘Ain al-Hilweh adjacent areas; American University of Beirut in Spring 2013. Course instructor is Marwan Ghandour with Mona Fawaz as a visiting critic and Salwa Sabbagh as a graduate assistant. Fourteen students enrolled in the course, their names appear in the acknowledgment paragraph.

[3] These figures are included in map 30 of the master plan of Saida project by Michel Ecochard and his team. The map title is “Localization des Zones d’Extension Surf. et Densites”. Amin al-Bizri archives, courtesy of Fadi Kotob.

[4] See “Building Programme for the Relocation of 1000 Families in ‘Ain el Helwe Saida;” undated preliminary report prepared by Wilson Garces, Housing and Planning Consultant, U. N. T. A. A. in collaboration with Dr. Lucien Dahdah, Mr. Emile Masabni, Mr. Munther Khatib, and Dr. Jean Mourad of the National Reconstruction Board. Amin al-Bizri archives, courtesy of Fadi Kotob. See also"مشروع إدارة التعمير في صيدا الجديدة" …

[5] The camp includes a large number of political parties that range from Salafist (Islamic extremist) such as Jund al-Sham and Usbat al-Ansar, Islamic resistance such as Hamas, as well as the historical parties of Fateh, Sa‘iqa and the Marxist parties of PFLP and DFLP. See “A world not Ours” a film production by Nakba Filmworks by Mahdi Fleifel.